Why Value Engineering Is the Key to Competitive Manufacturing

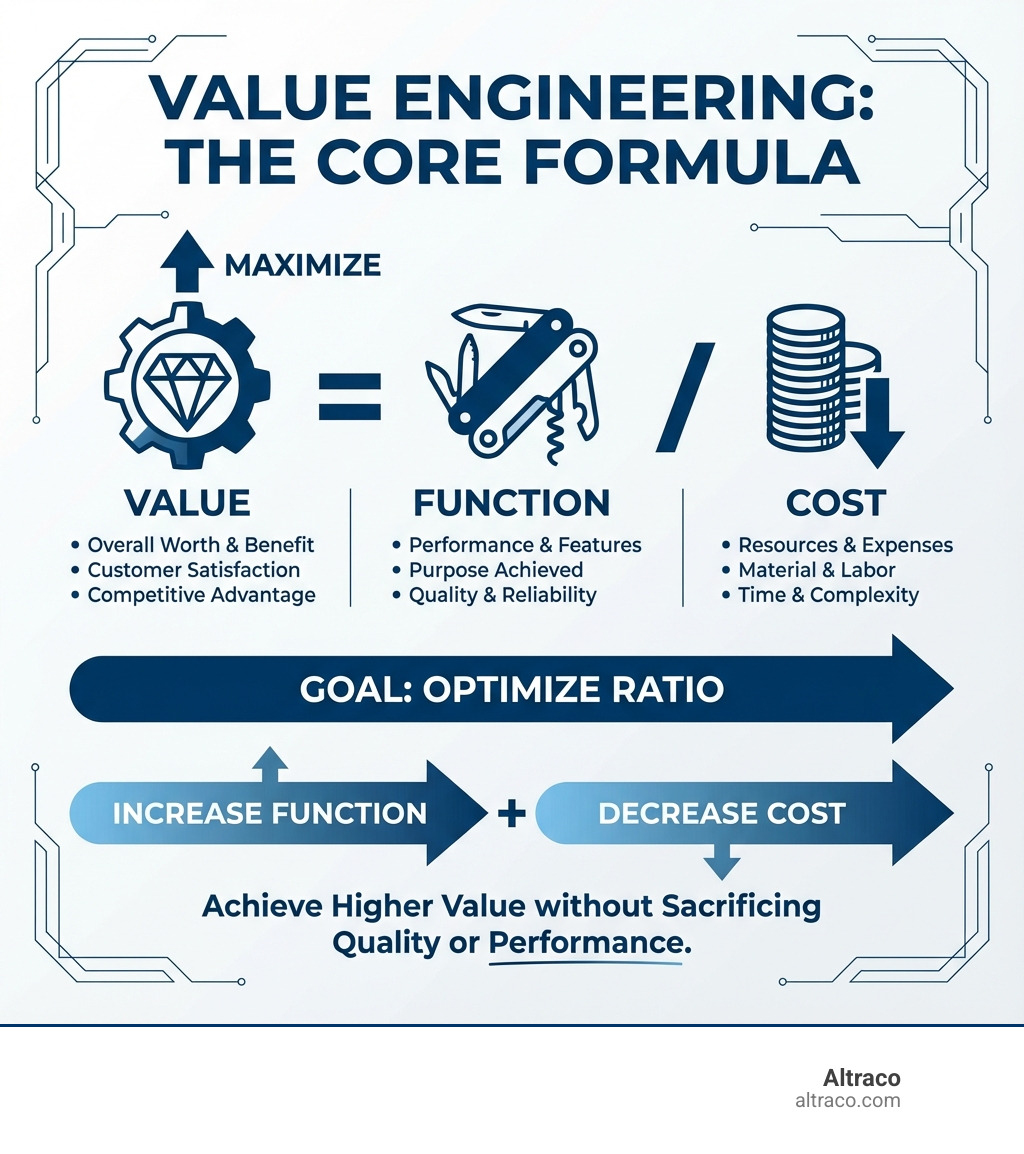

Value engineering is a systematic method to improve the “value” of products by analyzing their functions. The core principle is simple: Value = Function / Cost. By either increasing a product’s function or decreasing its cost—without sacrificing quality—manufacturers can deliver better products at lower prices.

Quick Definition:

- What it is: A structured process to analyze product functions and eliminate unnecessary costs while maintaining or improving quality

- Primary goal: Maximize value by optimizing the function-to-cost ratio

- When to use it: Most effective during the design phase, but applicable throughout the entire product lifecycle

- Key benefit: Reduces costs, improves quality, and increases profitability without compromising performance

The concept originated during World War II at General Electric when material shortages forced engineers to find substitutes. They finded that these alternatives often performed better than the original materials at lower costs. This accidental findy evolved into a formal methodology that has saved billions of dollars across industries—the U.S. Department of Defense alone has saved over $47 billion through value engineering since 1981, with an average return on investment of sixteen to one.

For companies manufacturing products offshore, value engineering is more critical than ever. With tariff uncertainties—including recent Supreme Court decisions affecting international trade—and complex global supply chains, optimizing the function-to-cost ratio can mean the difference between profit and loss. Value engineering helps you identify which product features truly matter to your customers, which manufacturing processes add unnecessary complexity, and where smarter design choices can reduce costs without compromising quality.

The methodology isn’t just about cutting costs. It’s about asking fundamental questions: What does this component actually do? Is there a better way to achieve the same function? Are we over-engineering this part? These questions become especially important when manufacturing home improvement products, sporting goods, automotive parts, or outdoor equipment in countries like Mexico, China, or Vietnam, where design decisions directly impact tooling costs, material expenses, and shipping logistics.

I’m Albert Brenner, and over 40 years in contract manufacturing, I’ve applied value engineering principles to help Fortune 500 companies optimize their offshore production across multiple countries. Whether navigating tariff challenges or streamlining product designs for more efficient manufacturing, value engineering has consistently delivered measurable results for our clients.

The Foundations: History, Principles, and Core Concepts

This section explores the origins of value engineering, its guiding principles, and how it differs from related methodologies.

The story of value engineering begins, as many great innovations do, out of necessity. During World War II, many industries faced severe shortages of skilled labor, raw materials, and component parts. At General Electric Co. in the 1940s, a visionary engineer named Lawrence D. Miles, along with Harry Erlicher, was tasked with finding acceptable substitutes for scarce materials. What they finded was remarkable: these substitutions often not only reduced costs but also improved product performance and reliability. This wasn’t mere cost-cutting; it was a systematic way to achieve better value.

Miles formalized this accidental findy into a methodology initially called “value analysis.” As the U.S. Navy later adopted these techniques for project improvement in the early 1950s, the term “value engineering” emerged, emphasizing its application during the design and development phases of new products or projects. This historical context highlights a crucial point: value engineering is fundamentally about innovation and improvement, not just reduction.

Core Principles of the Value Methodology

At its heart, value engineering operates on several core principles that guide its application:

- Function-Oriented Approach: This is perhaps the most distinctive principle. Instead of focusing on what a product is or how it’s made, value engineering asks what function a product or component performs. Functions are defined using a two-word active verb and measurable noun (e.g., “provide light,” “transmit power,” “secure panel”). This objective analysis helps uncover alternative ways to achieve the same function more efficiently.

- Cost-Worth Analysis: Every function has an associated cost. Value engineering carefully examines these costs against the “worth” of the function—what it’s truly contributing to the overall value of the product or project. This ensures that resources are allocated to functions that deliver the most value.

- Preserving Basic Functions: A primary tenet of value engineering is that basic functions must be preserved and not reduced. While secondary functions (those that provide esteem, dependability, or convenience) can be optimized or eliminated, the core purpose of the product must remain intact or be improved. We’re not just stripping away features; we’re making sure the essential purpose is met optimally.

- Client-Centricity: The ultimate measure of value lies with the customer or end-user. Successful value engineering always keeps the client’s needs and perceived value at the forefront, ensuring that any changes improve their satisfaction.

- Systematic Process: Value engineering isn’t a haphazard approach. It follows a structured, multi-phase job plan, ensuring thorough analysis, creative problem-solving, and rigorous evaluation.

- Innovation: By challenging assumptions and exploring alternative ways to achieve functions, value engineering fosters a culture of innovation. It encourages brainstorming and out-of-the-box thinking to find novel solutions.

- Multidisciplinary Teams: Effective value engineering requires diverse perspectives. Teams typically include experts from engineering, design, manufacturing, finance, and marketing, bringing a holistic view to the problem.

- Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA): Decisions in value engineering consider not just the initial purchase or production cost, but the total cost of ownership over the product’s entire lifespan, including maintenance, operation, and disposal.

Value Engineering vs. Value Analysis

While often used interchangeably, value engineering (VE) and value analysis (VA) have a subtle but important distinction, primarily related to their timing in a product’s lifecycle. Think of them as two sides of the same coin, both aiming to improve the function-to-cost ratio.

| Feature | Value Engineering (VE) | Value Analysis (VA) |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Proactive: Applied during the design and development phase of a new product or project. | Reactive: Applied to existing products, processes, or services already in production or use. |

| Primary Goal | Cost avoidance: To prevent unnecessary costs from being designed into a new product. | Cost reduction: To identify and eliminate unnecessary costs in an existing product. |

| Application | New product design, concept development, early-stage project planning. | Existing products, manufacturing processes, operational procedures, value stream optimization. |

| Focus | Optimizing initial design for maximum value and minimum life-cycle cost. | Improving existing products based on real-world feedback on features, manufacturing complexity, and operating efficiency. |

| Nature | Preventative | Remedial |

We apply value engineering when we’re helping clients with a New Product Introduction, ensuring that the design is optimized for cost-effectiveness and manufacturability from day one. In contrast, value analysis comes into play when we’re reviewing an existing home improvement product or outdoor gear line, looking at real-world feedback to understand which features truly resonate with the market, which complicate manufacturing, and which reduce operating efficiency. Both are powerful tools in our arsenal to improve profitability and sustainability for our partners.

The Value Engineering Job Plan: A Step-by-Step Guide

To ensure a systematic and thorough approach to maximizing value, value engineering follows a structured, multi-phase process known as the Job Plan. This methodical framework, often promoted by organizations like SAVE International, guides teams through analysis, creativity, and implementation.

The Job Plan is typically composed of six core phases, though some variations may include more detailed steps. These phases integrate seamlessly into comprehensive project management, especially during the critical stages of New Product Introduction.

Phases 1-3: Information, Function Analysis, and Creativity

These initial phases lay the groundwork for identifying opportunities and generating innovative solutions.

- Information Gathering: This is where we collect all relevant data about the product or project. This includes comprehensive cost data (design, materials, manufacturing, maintenance, disposal), specifications, drawings, performance requirements, and market research. The goal is to understand the “as-is” state thoroughly. For instance, when looking at an automotive part, we’d gather data on material costs, machining time, assembly steps, and any warranty claims. This phase is about developing a deep understanding of the problem space, leaving no stone unturned.

- Function Analysis: This is the heart of value engineering and its unique differentiator. Here, we systematically define the functions of the product and its components, typically using a two-word active verb and measurable noun. For example, a car door’s function might be “provide access” and “protect occupants.” We then categorize functions as “basic” (essential purpose) or “secondary” (supporting the basic function). Tools like Function Analysis System Technique (FAST) diagrams are often used to graphically represent these functions and their relationships, helping us visualize dependencies and identify where value might be lacking. This focused approach helps us understand what the product does, rather than what it is.

- Creativity (Brainstorming): With a clear understanding of functions and costs, the team moves into generating alternative ways to perform those functions. This is a free-wheeling brainstorming session where judgment is suspended to encourage a wide range of ideas, no matter how unconventional. The goal is quantity over quality initially. For a home improvement product, this might involve exploring different materials, manufacturing processes, or design configurations to achieve the same function. We might ask, “How else can we ‘provide light’ or ‘secure panel’?”

Phases 4-6: Evaluation, Development, and Implementation

Once ideas are generated, the focus shifts to refining and bringing the best solutions to fruition.

- Evaluation: In this phase, the ideas generated during brainstorming are critically assessed. We evaluate each alternative against criteria such as technical feasibility, cost savings potential, impact on quality and performance, ease of implementation, and alignment with client needs. Risk assessment is crucial here; we consider potential downsides or unintended consequences. This is where we narrow down the vast array of ideas to a select few with the highest potential for value improvement.

- Development: The selected ideas are now developed into detailed proposals. This involves refining designs, creating specifications, quantifying cost savings, and projecting performance improvements. We prepare comprehensive documentation that outlines the proposed changes, the rationale behind them, and the anticipated benefits. For an outdoor product, this might involve creating prototypes or detailed CAD models of a redesigned component. The aim is to provide stakeholders with enough information to make informed decisions.

- Presentation and Implementation: The developed proposals are presented to management and other key stakeholders for approval. The presentation should clearly articulate the problem, the proposed solution, the benefits (quantified cost savings, quality improvements, etc.), and any associated risks. Once approved, the changes are implemented. This phase also includes performance monitoring to ensure that the actual benefits align with the projections and that the implemented changes meet all requirements without introducing new problems. This continuous feedback loop is vital for learning and refining our value engineering processes.

Tools, Techniques, and Real-World Impact of Value Engineering

Value engineering relies on a suite of practical tools and techniques to systematically analyze and improve products and processes. These tools, combined with a structured methodology, allow us to deliver tangible results, from significant cost savings to improved product quality.

Essential Tools and Techniques for Effective Value Engineering

Our approach to value engineering involves a blend of analytical and creative tools:

- Function Analysis System Technique (FAST): As mentioned, FAST diagrams graphically represent the logical relationships between functions. They help us understand “how-why” functions are performed, clarifying complex systems and identifying areas where functions might be redundant or inefficient.

- Brainstorming: A cornerstone of the creative phase, brainstorming is used to generate a large volume of ideas for achieving functions differently or more efficiently. It encourages diverse thinking and suspension of judgment.

- Benchmarking: This involves comparing the product’s functions, processes, and costs with industry best practices or competitor offerings. It helps identify areas where we can improve or adopt more efficient solutions.

- Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA): Critical for long-term value, LCCA evaluates the total cost of ownership over a product’s entire lifespan, including initial purchase, operation, maintenance, and disposal. This ensures that short-term cost savings don’t lead to higher costs down the road.

- Pareto Analysis: Also known as the 80/20 rule, Pareto analysis helps identify the few critical items (e.g., components, processes, cost drivers) that account for the majority of the cost or problems. By focusing our value engineering efforts on these high-impact areas, we can achieve maximum results with optimized effort.

- Design of Experiments (DOE): This statistical technique helps us plan, conduct, and analyze controlled tests to understand how different factors influence a product’s performance or cost. It’s particularly useful for optimizing manufacturing processes for automotive parts or home improvement goods.

- Function-Cost Matrix: This tool links specific functions to their associated costs, allowing us to quickly identify functions that are disproportionately expensive relative to their value.

At Altraco, these tools are invaluable, especially when we are engaging in International Sourcing Services and need to evaluate potential suppliers or manufacturing processes. We also integrate these insights into our Supplier Scorecards to continuously monitor and improve the value delivered by our partners.

Real-World Examples: Successes and Cautionary Tales

The impact of value engineering is evident across countless projects and industries, with both inspiring successes and stark warnings about its misapplication.

Successes:

- The Golden Gate Bridge: Completed at approximately $35 million, significantly reduced from its original budget of $100 million. This monumental saving was achieved through early application of value engineering principles, including material substitution, design simplification, and innovative construction techniques. Imagine the impact of applying similar rigorous analysis to today’s large-scale manufacturing projects.

- JCI’s HVAC Division: By applying value engineering principles within a collaborative platform, JCI was able to quadruple engagement and double actionable ideas, leading to the delivery of 8-figure targets in consecutive years. This demonstrates how modern tools can amplify the effectiveness of VE.

- Tensar Geogrids in Construction: In various construction projects, the use of Tensar geogrids, a material solution, demonstrated significant cost savings through value engineering. For instance, on the Axbridge Road project, geogrids saved £86,000 in construction costs by improving structural integrity. Similarly, at the Orchard Place housing scheme, they saved £64,000 on flexible pavement construction and achieved a 33% reduction in imported fill. Even at the Whitelee Wind Farm, geogrids eliminated the need for costly peat excavation and aggregate replacement, reducing overall aggregate volumes. These examples, though in construction, highlight the power of material substitution and process optimization—principles directly applicable to manufacturing home improvement or outdoor products.

- U.S. Department of Defense: The U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Ships established a formal program in 1957, and by 1992, the GAO recommended its adoption by “all federal construction agencies.” The DOD has collectively saved billions by applying VE across its vast network of systems and supplies, from redesigning aircraft components to optimizing maintenance schedules.

Cautionary Tales: The Grenfell Tower Tragedy

A critical example that highlights the dangers of misapplying value engineering is the Grenfell Tower fire in London. The inquiry heard that non-combustible zinc panels were swapped out for cheaper aluminum composite material as part of a “value engineering exercise” to save nearly £300,000. This substitution of higher-quality, fire-resistant materials with cheaper alternatives was widely seen as accelerating the tragic fire, leading to the UK inquiry report being “highly skeptical of the whole endeavor of value engineering,” stating it is “in practice little more than a euphemism for reducing cost.”

This devastating event serves as a stark reminder: value engineering is not about indiscriminate cost-cutting. It’s about maintaining or enhancing function and quality while optimizing costs. When quality and safety are compromised for the sake of a lower price, the methodology is fundamentally misused. As we dig into A look at the Grenfell refurbishment, we see the critical importance of ethical and function-focused application of VE principles.

Benefits, Challenges, and the Role of Professional Bodies

Value engineering offers substantial advantages but also comes with its own set of problems.

Benefits:

- Cost Reduction and Avoidance: This is the most direct and frequently cited benefit. By identifying unnecessary costs in design, materials, or processes, VE can lead to significant savings.

- Product Improvement: Often, the analytical process of VE leads to improved quality, performance, reliability, and even marketability of products.

- Increased Profitability: By reducing costs and improving products, VE directly contributes to higher profit margins.

- Improved Customer Satisfaction: Better-designed, more efficient products that meet customer needs more effectively lead to happier customers.

- Innovation: The creative phase of VE encourages novel solutions and breakthroughs.

- Streamlined Processes: VE can identify inefficiencies in manufacturing or operational processes, leading to smoother, faster production.

- Sustainability: By optimizing material use and reducing waste, VE contributes to more sustainable manufacturing practices.

Challenges:

- Resistance to Change: People are often comfortable with existing methods. Overcoming inertia and convincing stakeholders to adopt new approaches can be difficult.

- Time-Consuming: A thorough value engineering study requires dedicated time and resources, which some organizations may be reluctant to invest upfront.

- Balancing Cost and Quality: The Grenfell Tower incident painfully illustrates this challenge. It’s crucial to ensure that cost reductions do not compromise essential functions, safety, or quality.

- Lack of Expertise: Effective VE requires skilled facilitators and multidisciplinary teams, which may not always be readily available internally.

- Defining “Function”: Objectively defining and agreeing upon the core functions of a product can sometimes be challenging, especially for complex or abstract items.

The Role of Professional Bodies:

Organizations like SAVE International (originally the Society of American Value Engineers, established in 1959) play a crucial role in promoting and standardizing value engineering. They provide education, certification (like Certified Value Specialist – CVS), and a platform for professionals to share best practices. SAVE International’s “Value Standard and Body of Knowledge” provides a framework for applying the methodology consistently and effectively.

Furthermore, value engineering has strong governmental backing in the U.S. It is mandated for federal agencies by section 4306 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1996. The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) part 48 provides direction to federal agencies on the use of VE techniques, and OMB Circular A-131, issued in May 1993, required all federal agencies to use VE and report on VE practices annually. These mandates underscore the recognized importance of VE in achieving cost-effectiveness and efficiency in public projects, from construction to defense procurement.

Frequently Asked Questions about Value Engineering

What is the main difference between value engineering and value analysis?

The primary distinction lies in timing. Value engineering is a proactive process applied during the design and development phase of a new product to prevent unnecessary costs from being designed in. It focuses on optimizing the initial design for maximum value and minimum life-cycle cost. Value analysis, on the other hand, is a reactive process used on existing products, processes, or services already in production or use. Its goal is to identify and eliminate unnecessary costs without compromising function, often based on real-world feedback. Think of VE as “getting it right from the start” and VA as “improving what’s already there.”

Is value engineering just about cutting costs?

No, absolutely not. While cost reduction is a significant and often sought-after outcome, the true goal of value engineering is to improve value, defined as the ratio of function to cost (Value = Function / Cost). This can be achieved in several ways:

- Reducing cost for the same function: This is the most common perception, but it must be done without sacrificing quality or performance.

- Increasing function for the same cost: Adding more beneficial features or capabilities without increasing expense.

- Increasing function for a slightly higher cost: If the added function significantly improves the product’s overall value proposition, a slight cost increase can still improve the Value ratio.

It is a function-focused methodology, not a simple cost-cutting exercise. The process rigorously ensures that basic functions are preserved and that any changes lead to a net improvement in value for the customer. The unfortunate misuse of VE, as seen in the Grenfell Tower tragedy, highlights the critical importance of maintaining this focus on function and quality.

When is the best time to apply value engineering?

Value engineering delivers the greatest return on investment and achieves the most significant impact when applied as early as possible in a project’s lifecycle, ideally during the concept and design phases. This is because changes made at these early stages are far less expensive and disruptive than modifying tooling, processes, or products that are already in production. The cost of making a change escalates dramatically as a project progresses. Implementing VE early allows for fundamental shifts in design, material selection, or manufacturing processes that can avoid costs altogether, rather than trying to reduce them later. While VE can be applied at any stage of a product’s lifecycle (where it often becomes value analysis), its preventative power is maximized at the outset.

Conclusion: Maximizing Value in Your Global Supply Chain

Value engineering is more than just a buzzword; it’s a systematic methodology that empowers manufacturers to consistently deliver superior products at competitive prices. By carefully analyzing functions, optimizing costs, and fostering innovation, VE drives both profitability and customer satisfaction. It’s about asking the right questions at the right time to open up hidden value in every design, material, and process.

In today’s dynamic global market, where supply chains are intricate and economic pressures, such as tariffs, are ever-present, the principles of value engineering are indispensable. For companies manufacturing home improvement, sporting goods, automotive parts, or outdoor products, especially through offshore contract manufacturing in regions like Mexico, China, or Vietnam, a robust VE strategy can be a game-changer. It enables us to steer complexities, mitigate tariff impacts through smart design and sourcing, and ensure that every dollar spent contributes maximally to product value.

As your strategic Manufacturing Partner, we at Altraco understand that successful offshore production hinges on more than just finding a factory. It requires a deep understanding of value engineering to optimize designs, streamline manufacturing processes, and carefully manage costs across the entire supply chain. Our decades of experience, trusted factory relationships, and expertise in tariff navigation allow us to apply these principles to deliver quality, on-time products with significant cost savings for our clients.

We invite you to explore how our Services can optimize your manufacturing process, improve your product’s value, and deliver unparalleled results in your global supply chain.